The other day, Nation Africa published a feature on ‘How rogue Pharmacists are robbing the sick’ that highly emphasised the existing price exploitation by pharmaceutical outlets. According to this report, in the retail sector, essential medicines are marked up by over 300%. This further complicates access to life-saving medicines, pushing patients to the point of opting to skip their medicines, as they have to dig deeper into their pockets, negatively impacting adherence to treatment and ultimately resulting in mortalities. This was highly attributed to the lack of a regulatory framework in the free market drug pricing policy in Kenya. While some of the findings may be slightly exaggerated, it is evident that there are no policies in Kenya that inform and guide the pricing of medicines. (Ongarora et al., 2019) Further, the Kenya National Pharmaceutical Policy defines the scope of essential medicines and outlines key strategies to ensure that they are available and affordable but does not specifically address the issue of pricing. (Ministry of Medical Services, 2012)

In Kenya, medicine prices directly affect affordability and access to medicines since a major portion of pharmaceutical spending is through out-of-pocket healthcare payments at the point of service. This is mostly due to the low availability of medicines in publicly funded healthcare facilities. (Paola et al., 2019) Research done by Wamae et al. underscored the fact that pharmaceutical expenditure is on the rise in Kenya, as is health expenditure, with only about 50% of essential medicines available in public healthcare facilities. Consequently, the private sector health facilities and wholesale and retail outlets have stepped in and set their pharmaceutical prices independently on a full cost recovery basis. There is an overarching dependence on the private health sector for essential medicines. Access to quality-assured essential medicines in Kenya continues to remain a challenge. (Vugigi et al., 2019)

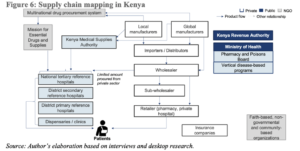

This report also unveils a common barrier to access to medicines: The supply chain. Medicine procurement in the Kenya public health sub-sector is mainly through the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA), a state corporation established under the Laws of Kenya, the KEMSA Act of 2013. (Toroitich et al., 2022) The procurement process is governed by the KEMSA Act, the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act of 2015, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) procurement guidelines. Specifically, the procurement of pharmaceutical products is anchored on the principle of the lowest bidding price. Based on the economies of scale, the prices of medicines procured by KEMSA tend to be cheaper. This approach targets value for money, prevents overpaying for a product that is readily available in the market, and ensures accessibility of pharmaceuticals in public health facilities at affordable prices.

A study on Pharmacy practice in Kenya reported that in a public facility, a patient might access the medicine either free of charge or at a subsidised cost within the facility. While the private sector equally provides health services, including medicines, it does so on a full cost-recovery basis. Publicly procured medicines for priority health programs are provided free of charge through public and faith-based healthcare(FBO) facilities. This includes contraceptives, and HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis medicines. (Aywak et al., 2017) Additionally, most public facilities and FBOs are beneficiaries of Medicines Access Programs (MAPs) and are offered medicines by pharmaceutical companies, who act as sponsors to facilitate deferred cost, cost-free or subsidised access to medicines for hospital patients. Access programs to Medicines for Non-Communicable Diseases in Kenya, e.g. Diabetes, Hypertension and Cancer, by pharmaceutical companies like Novartis have had significant price reductions for the medicines. This explains why a patient can get insulin(Mixtard) for free/at a subsidised cost in a public hospital, but in a retail pharmacy, they have to buy it at a higher price.

With the pharmaceutical sector being highly fragmented with intense competition involving local and foreign pharmaceutical manufacturers, importers, warehousing agencies, distributors, wholesale pharmacies, and retail pharmacies/chemists, it is close to impossible for them to match up the public sector retail prices. A policy analysis paper on increasing access to basic medicines through the private sector supply chain in Kenya revealed that most retail pharmacies have high retail markups, with a lack of price competition mostly attributed to information asymmetry. This analysis paper highlights a noticeable price variation even with retail pharmacies within the same area, strongly suggesting the possibility of an existing barrier to price discovery and/or other drivers determining medicine prices. (Paige Taylor, 2023)

That being said, the public sector also benefits from grants and further discounted prices driven by the quantities they procure. In addition to government subsidies, the public sector can comfortably thrive by selling medicines below market rates. Such an attempt would be catastrophic to a private investor who must recover the cost of buying the drugs and meet the overhead costs of the business to replenish their stocks.

In light of the article by Nation Africa, the following takeouts are key:

- By no means can the retail prices in a public health facility/FBO be similar to those in a private retail pharmacy.

- The different brands existing in the market have different prices. The price of an innovator molecule is higher than that of a generic molecule.

- There will always be different price variations when comparing different therapeutic categories. E.g. antihypertensives, antibiotics, etc. Also, contrary to Nation Africa’s article, the price of Mixtard cannot be compared to that of Lantus as those are two different insulin formulations.

- In the private sector, every pharmacy sources its medicines differently. For instance, currently, the market has many small-scale wholesalers, which increases last-mile costs and adds middlemen, resulting in a higher cost price that eventually trickles down to the patient.

The overarching need for policy reforms that inform the pricing of medicines cannot be overemphasised. Major industry shifts are urgently needed, but the most important aspect that should be addressed is the retailer pricing power. Regardless of the approach taken, price transparency is key.

There are definitely pertinent issues in the pricing of pharmaceutical products that I believe the Government and the regulator (Pharmacy and Poisons Board) should look into, but the title of this specific article, ‘How rogue pharmacists are robbing the sick’, by Nation Africa, was quite misleading.

Written & compiled by:

Dr. Maryanne Ong’udi

REFERENCES

- Ongarora D, Karumbi J, Minnaard W et al. Medicine Prices, Availability, and Affordability in Private Health Facilities in Low-Income Settlements in Nairobi County, Kenya. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(2). [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6631117/.

- Ministry of Medical Services MoPHaS. Kenya National Pharmaceutical Policy. Nairobi (Kenya): [Internet]. 2012. [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: https://repository.kippra.or.ke/handle/123456789/1165#:~:text=It%20provides%20for%20the%20legal,the%20procurement%2C%20supply%2C%20regulation%20and.

- Paola S, Laura Di G, Stefania I et al. The catastrophic and impoverishing effects of out-of-pocket healthcare payments in Kenya, 2018. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(6):e001809. [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: http://gh.bmj.com/content/4/6/e001809.abstract.

- Vugigi SK, W. Keter, F. Pharmaceutical Partnerships for Increased Access to Quality Essential Medicines in the East Africa Region.: [Internet]. 2019. [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: http://ir.kabarak.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/123456789/545/Pharmaceutical%20Partnerships.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Toroitich AM, Dunford L, Armitage R et al. Patients Access to Medicines – A Critical Review of the Healthcare System in Kenya. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;15:361-74. [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8898182/.

- Aywak D, Jaguga CDP, Nkonge NG et al. Pharmacy Practice in Kenya. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017;70(6):456-62. [accessed: 07 March 2024]. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29299006/.

- Paige Taylor. Increasing access to basic medicines through the private sector supply chain in Kenya and Tanzania. [Internet]. 2023. [accessed: Available at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/SYPA_2023_Taylor_A.pdf.